Tai Shani

The Neon Hieroglyph

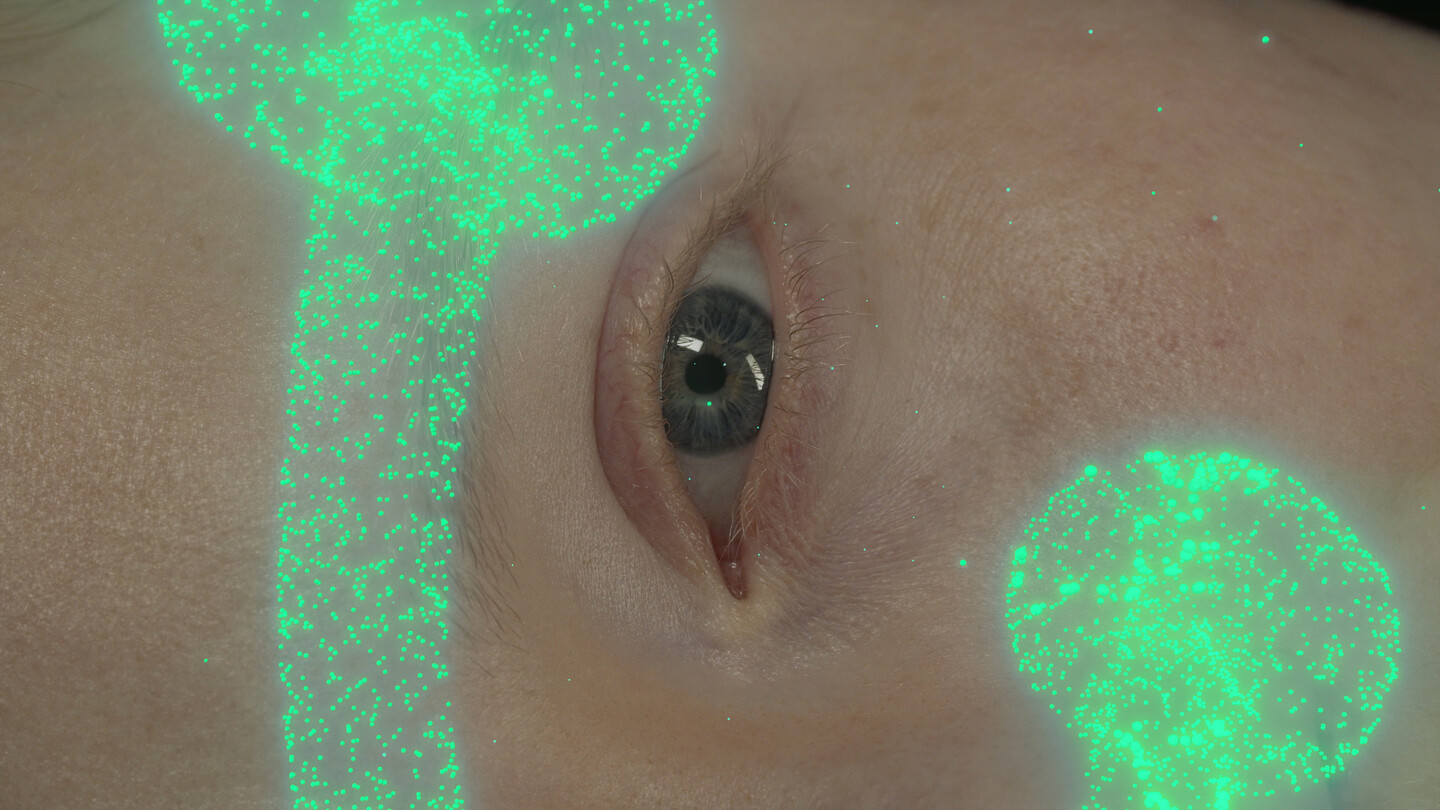

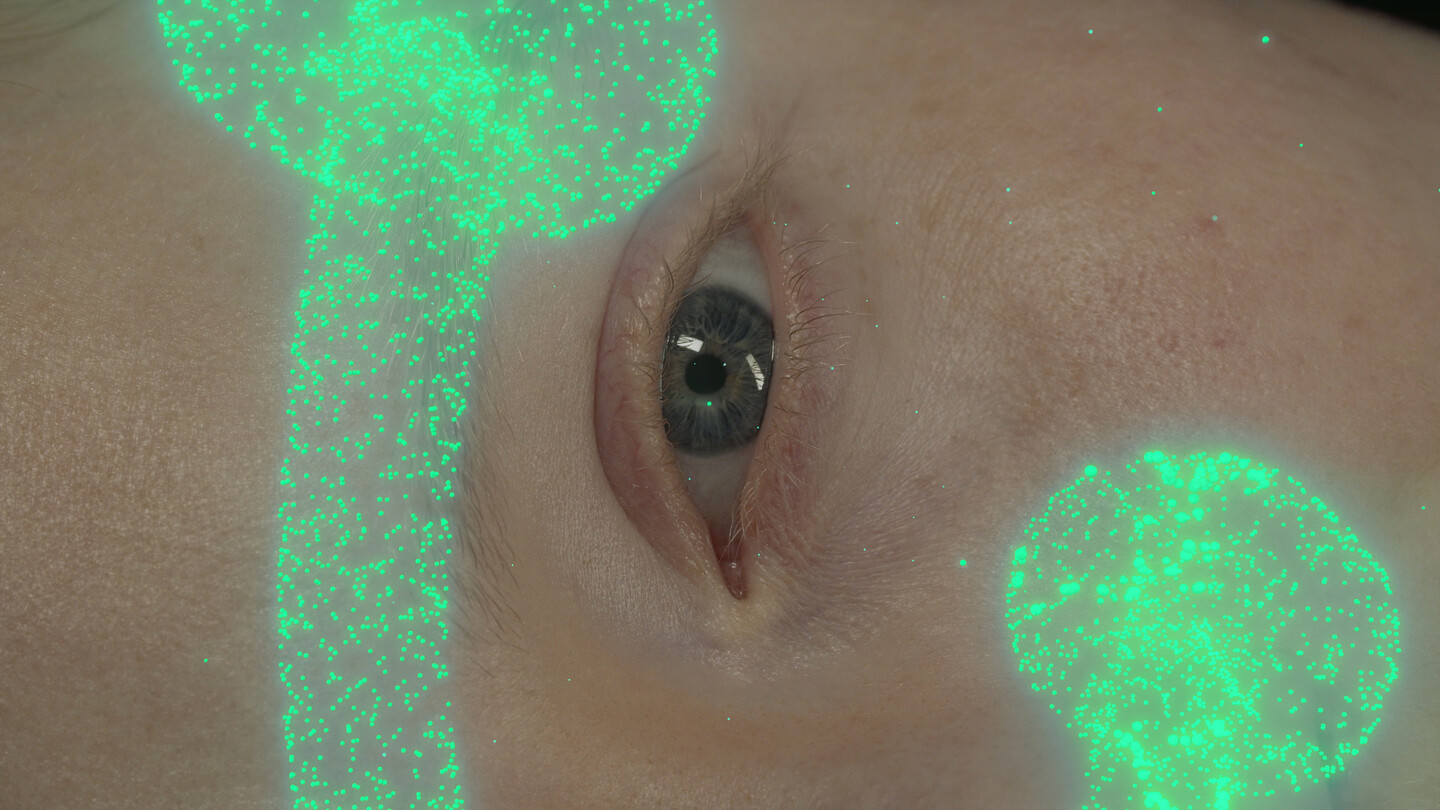

Tai Shani, still from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Manchester International Festival.

Because categories like certainty and uncertainty are all tied up with time, self-consciousness and the past, I think that exploring and communing with the past is a way of approaching the idea of the future. That’s why I’m so interested in the histories of ergot, of “Alicudi nel cielo” and myths about the sea, though they’re so at the edge of time.

These histories are incredibly certain in their meaning for the people that they affected, but they are incredibly uncertain for us. I think we can make fantastic links between contemporary theory that’s very certain, like the kinds of psychoanalysis that are transhumanist or imagine a new future, and these really uncertain histories, populated by undead ideas. It’s not a kind of magical thinking, it’s a very sober, material way of thinking. I’m trying to bring together speculative mentalities and histories that are wrong.

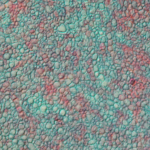

Sultry whirlwinds, rocks and donkeys, 820 steps above, the rustle of rye, silvery shivers of moonlight. Heading up to Saint Bartholomew’s church on Alicudi at this time of year is risky business: scuba divers drown, fishermen’s boats never return, tourists fall to their deaths. Craggy coastline dissipates under a flattened mountain top; the ruins of an old church are lit up bruise-blue by a full moon that slips out of the clouds. Looking out over the horizon, saturated with oceanic feeling, there you see them: the Maiara witches, returning from Palermo and the mainland with satchels stuffed with treats. Mirrored in the water, their skin is translucent, their hair phosphorescent. You look down at your outstretched hands over the knife’s edge of the cliffside and you too are glowing, flecks of freckles like stardust from fungal rye, in your bread, your milk, your blood, nourishing a lost magic—

Tai Shani, screen capture from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021.

Tai Shani works in the sticky space between myth and history, where the unknowability of the past gives way to a multiplicity of potential realities. Research into a women’s commune in the suburbs of Rome morphed into the artist’s discovery of Alicudi and its psychedelic entanglement with ergot: the small volcanic island, situated within the Aeolian archipelago off of Sicily, believes itself to have been poisoned with fungus-contaminated rye for the last 450 years. Though the climatic conditions to sustain this psychoactive fungus are incredibly particular – and in all likelihood, the self-contained society wasn’t tripping on ergot-laced grains since its establishment in the 1500s – the story is sewn deep into the cultural consciousness of the island. How do these speculative mythologies crystallize, and to what end?

“What I liked about these stories is that while everywhere else in Europe thinks of the witch as porous to evil, a wrecker of civilization,” reflects Shani, “but in the Aeolian Islands, this character is the total opposite. I was interested in how the witch in this shared and extended fantasy became this sort of socialist figure.”

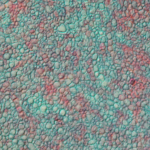

Shani’s fascination with the self-seeded mythology of Alicudi and its relationship to the psychedelic experience, alternative histories of witchcraft, and the materiality of altered states of consciousness, like the fungal spores of this devil rye – so named for the way purple-black fungal shoots grow out from the infected rye plant like horns – ultimately coagulated into The Neon Hieroglyph (2021). Split into nine loose episodes that are bookended by a hallucinogenic introductory animation, the fractured narrative fluctuates from macro to micro-focus, migrating from past to future, from molecular to interstellar. At the root of these hazy, incandescent episodes is an interest in the affective dimensions of the psychedelic experience – as a kind of porosity that splits open the self, abstracts language, and claws at a sensory intelligence of a universal awareness – and the latent political power of that feeling. ‘This feeling of being one with the external world as a whole exists in both psychoanalysis and philosophical-esoteric-mystical writing,” Shani suggests. “The Neon Hieroglyph was trying to create a communist affect by talking about psychedelic experiences or certain kind of senses that happen during them.”

Tai Shani, still from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Manchester International Festival.

I’m just thinking out loud now, I often wonder if there’s the possibility of learning how to write in a psychedelic state, in other words, to somehow teach language to its neural self?

I think there’s a part of the psychedelic experience that is not especially mediated by language: its much more about the body, it evokes embodied experiences. I would like to find a way of talking about certain kinds of physical movements, feelings and sensory phenomena, and the energies that aperceptually – or at least pre-cognitively – are there in these altered states of consciousness…

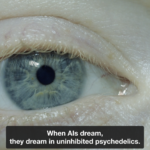

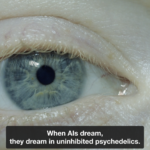

A psychedelic tone runs through The Neon Hieroglyph – dilated and wonderous, the universe marveling at itself. Episode four hones in close on a CGI eye crying pixelated tears. Clusters of stars shimmer in the sticky substrate of the iris: “we are lifted and stirred by a motion that animates all things,” reflects the narrator. “Within that motion, we touch and are touched by a harmony in which nothing is out of step.”

The next episode, loosely formed around a moment in The Eleusinian Mysteries where Persephone enters the underworld, has us doing the opposite: hovering, disembodied, up a flight of stairs within an empty suburban home. Entering a cobalt-carpeted bedroom washed in light, we inch closer to its single window. The camera pans outdoors to reveal an undulating trippy greenscape, which slowly inverts itself; zooming out, the swaying grass slowly morphs into the lips of the narrator, whose ego splits and melts into a CGI overlay of itself, eventually eclipsed by her digital avatar.

Tai Shani, screen capture from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021.

Desire is something that’s an interplay of words and thing, language and the unconscious. There are certain things that happen under the influence, like synaesthesia, where music becomes extremely heightened, or there’s something that switches off the id, so you experience empathy you couldn’t before – where you feel like you can transmit human feelings to a rock, or a tree, for example. Therefore there’s a sense that materiality as a shared field of experience is a key part of this.

Sensory excess is woven into the work, from its cosmic 3D-generated imagery to the shining, shuddering face of its AI-altered narrator/protagonist, who perpetually slips between real and digital personas. But the most arresting aspect of the work is Shani’s writing – The Neon Hieroglyph is principally a project of language, and a push to move beyond it. In thinking through the limits and ecstasy of words, Shani cites multiple overlapping references – from Jackie Wang’s idea of the Oceanic Feeling as communist affect, to Maurice Blanchot’s essay, “From Dread to Language” – and the poststructuralist feminist idea of “écriture feminine” – coined by Helene Cixous in the 80s as a project of writing excess into the world.

“It’s true that there’s a process of neutralization and diminishing of language,” says Shani. “But there’s also an opening up: writing can take a chaotic idea, or idea of affect, and opens it into a shared space of words. In my writing, words become portals or wormholes. It’s a different economy of words. In The Neon Hieroglyph I use Baroque lists of strange materials and colors – hearing them puts you in an affective and unfamiliar territory.””

Tai Shani, screen capture from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021.

Tai Shani, still from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Manchester International Festival.

To confront that and to fracture it with a new language is a feminist project. I associate femininity with excess, or a project of overflow. There is too much material in femininity to be contained, too much material to be fixed in a universal or ahistorical category.

Sometimes I’ll write something just to read it and see how well I can do it. In another ritual, in The Neon Hieroglyph, I read a series of lists of strange materials – ‘lithium hydroxide, ambergris, pyrite, syncope, gardenia’ in a loop, and those lists are written in two columns and the lists of quantities are mentioned twice, so there’s this doubling.

Our lives are filled with repetitions, and I liked the idea of reading out loud again and again. ‘Portal, portal, portal, portal.’ It’s a very simple system, but it creates a lot of affect. The repetitions have a historical and a temporal aspect – it’s repetitions as a means of forgetting. It was also interesting to think about how the series of series can contrast with the solitary act of saying it.

It’s said that within medieval Europe, when a large majority of the population was illiterate, people would flood the churches: not just to admire the light-washed stained-glass windows, or marvel at the cosmic curvature of the navel, but to listen to the Mass sermon – delivered in Latin – of which they couldn’t understand a word. The sound of scripture was ecstatic, hallucinogenic – the language of the gods – holy enough to get high in a cloud of unknowing.

I used the term “cloud of unknowing” in the closing statement to the performance. It’s not a term used very much now, and it’s a translation of a religious text from the 14th century, it’s this sort of a Western philosophical concept of the unknowability of God. And I used it as a way of illustrating this impossibility of knowing the past. But I do think that’s ultimately is more accurate than the terms we’re accustomed to hearing used like “objectivity,” “facts,” “knowledge,” etc.

Tai Shani, still from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Manchester International Festival.

“For every inscribed mythology, there’s a lost one as well,” says Shani. “How would you talk about the world if all you ever knew was the psychedelic experience?”

I’m interested in how certain feelings that can’t be wholly captured through the human language can be expressed through technology. When you’re writing a script for AI, it’s impossible to understand; you don’t have access to what the system is thinking.

Watching The Neon Hieroglyph, there are moments where the vivid vocabularies deployed by Shani give way to a diffuse sort of affect, something that hovers low on the horizon. Language flows in and flows out like the tide, cycling through you like phases of the moon, and you fall out of it a little, away from conscious earshot. The words dilate and peel away from their meaning; in other words, you become something like those churchgoers mid-rapture, or fumbling in conversation mid-trip. You become translucent. Language passes through you and other things enter the foreground – such as the voice of the transfiguring narrator: a kind of futuristic, placeless accent built through AI.

In The Neon Hieroglyph, the actor Molly Moody became an organic algorithm filter that snubbed out bits of her natural accent. Adding other accents – American, Scottish – to other words, it becomes this completely untraceable voice – a kind of futuristic speech, an amalgamation of different tongues, existing in this threshold space that’s both alienating and arresting.

I established a writing practice, called the autobiographical fallacy, which consisted of copying the tone of the patient notes of the psychotherapist I was seeing, and then pasting a couple paragraphs from my life, or a conversation I’d had with someone important, like my mother, into those notes, and then the therapist would reply to those semi-random sentences. The interaction between my therapist and these AIs, between these human and AI characters, became the performance piece. “Autobiographical Fallacy” was trying to explore this feeling of your lover leaving the country. How do you mourn someone who leaves?

For me, the AIs were just a way to capture the feeling of someone who’s gone in a way that’s not melodramatic of romantic; there’s an eerie feeling of someone’s left and you’ll never see them again. And in AI playfulness and uncertainty, there’s a sense that not even the AIs are sure they’re gone.

Tai Shani, screen capture from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021.

The Neon Hieroglyph is not Shani’s first experiment with AI to weird the world of her work. DC: Semiramis (2019) – a monumental, five-year undertaking inspired by an experimental proto-feminist text from the 15th century – imagines a speculative city of women heralded over by AI characters. One sequence of DC’s episodic narrative is told by an AI situated at the end of the universe, known as Mnemesoid. As the world’s non-hierarchical disembodied historical data aggregate, Mnemesoid allows users to replay her synthesized historical memories from any perspective: human, animal, amoeba, object. Another episode presents Psy Chic Anem One: a time-traveling AI with no body but an interface, an open-source oracle from the “anarchical beyond” that’s partially inspired by Shani’s interest in web-based oracle systems, from the Online Oracle of Delphi to Free Tarot and I-Ching. In another episode, a therapeutic AI harvests human genomic data to generate empathy faculties.

What I like about AI is to escape from what’s historically co-produced with humans and human forms of power. If we have a broken relationship with our body, what happens if the AI has a body?

Tai Shani, DC: Semiramis installation view at Tramway, Glasgow, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Spanning writing, performance, film, and a quasi-utopian, postmodern architectural installation of pastel hues and organic forms, DC merges physical and digital affect through these imagined AI systems, which try to reproduce or express the stickiest sort of feelings –profound self-consciousness, grief, fear, pain – that, in Shani’s words, “sit beyond the threshold of language”. Infusing AI with human subjectivities may be the highest desire of Silicon Valley circuits – a stab at anthropomorphism meant to soothe fears of an algorithmic takeover, known as the “manufactured normalcy field”– but what if this relationship was inverted, or the hierarchy flattened? How could AI expand or complicate not just the idea of being human, but embodiment and its political affect?

I liked how an AI body is this gigantic potentiality. I had a very strong relationship to this body (as matter) and for me, this concept of AIs as embodied was a liberating tool for me to talk about power, sex and sexuality, and all these things that are exposed to be consumed by power in the historical values of representation through image. Just as a thought of how we can represent our own existence and our own subjectivity under power, I was imagining AIs as the absence of that power. To have a body that would not be instantiated by the master’s body. A thought-body, an apparition, a flaking body that could be transported to another kind of space.

Tai Shani, screen capture from The Neon Hieroglyph, 2021.

In the ways that I wanted to use a body to represent something, I wanted a body that was like wet clay. Like a light, a fire that can be consumed, or it can remain there, and just melt into the space, just like the ghost of the time. Not like more than one body, but a body that could hold everyone and every thing.

Tai Shani in conversation with Serpentine’s Curator of General Ecology, Lucia Pietroiusti.