Patricia Domínguez

Madre Drone and Eyes of Plants

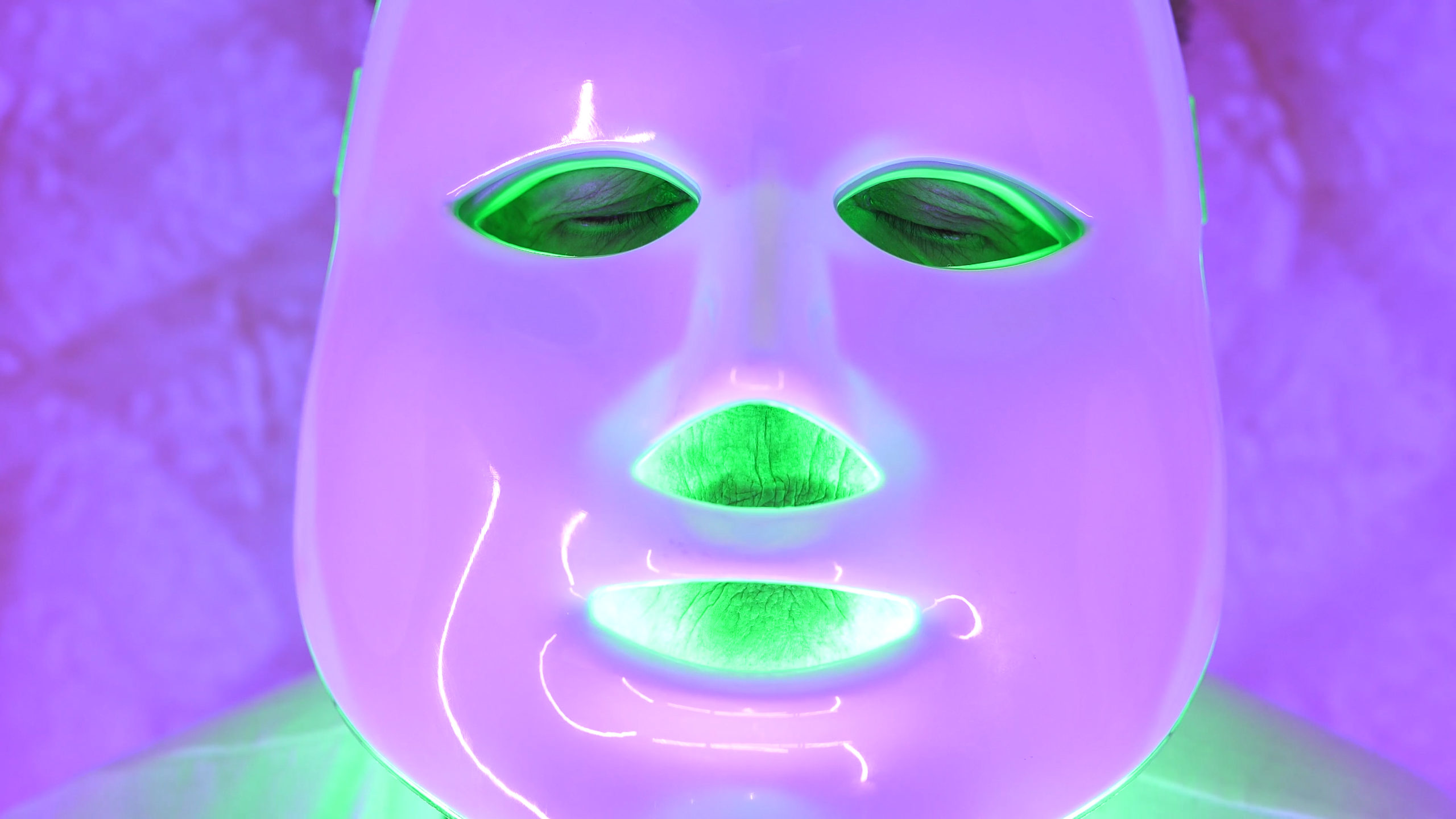

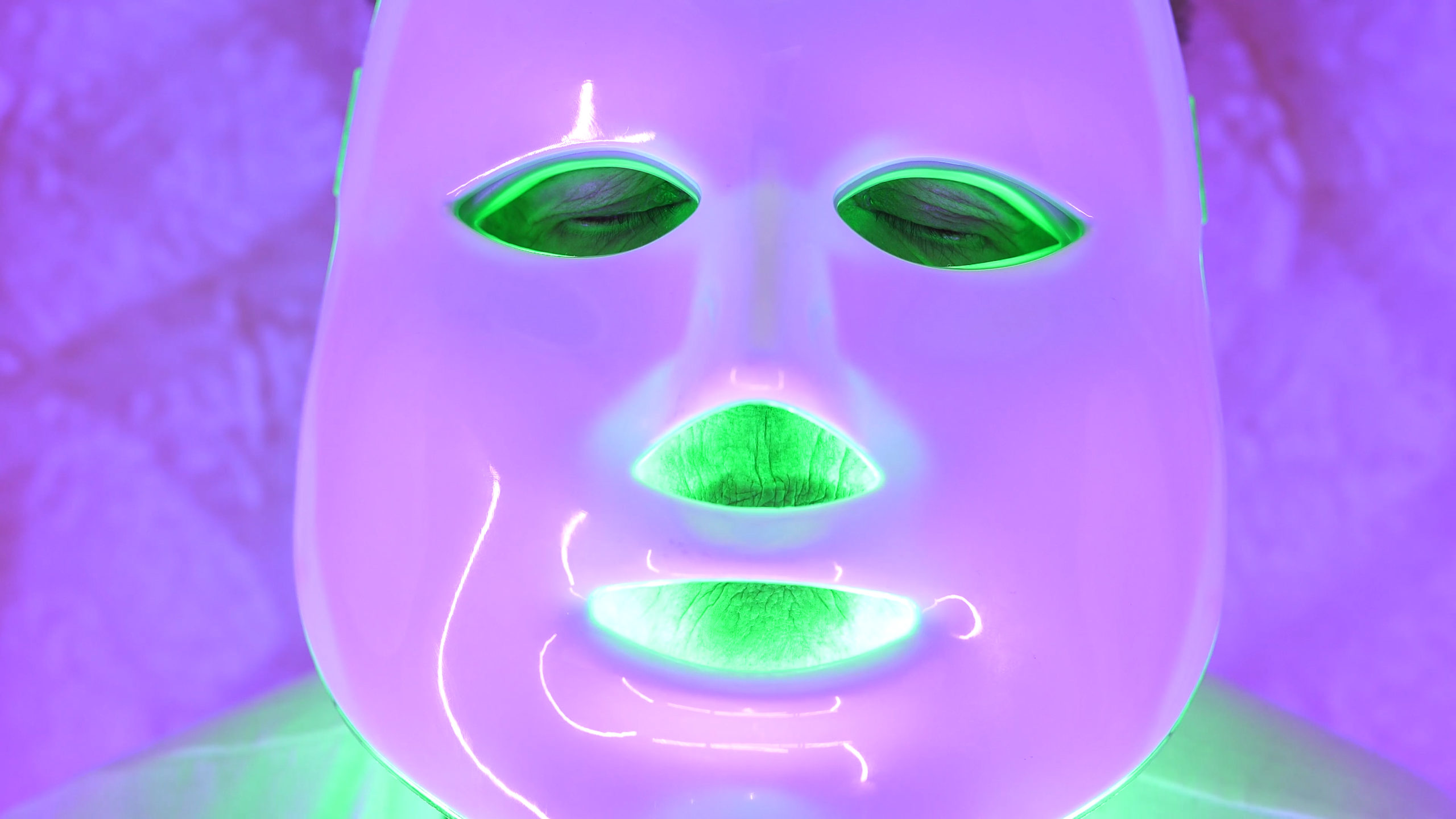

Patricia Domínguez, still from Eyes of Plants, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

I feel this need to bring the unseen, the unspoken of our time into the foreground of our being after the fall of the high eye of modernity and science and this exhaustion of the world and our bodies rationally speaking. But also this need for ritual, for ceremony, for healing, for agents, inspirational images or objects, new poetic forms or information that we can absorb into our neural paths through which we inhabit our own lives through our thoughts, as pixels of information coming into us from the universe. I think none of these are mutually exclusive.

We have the privilege of being here on this concentrated mass of emotion, of feeling, of thinking, of being on this planet, on this archipelago of islands on clouds in the universe. The universe is a field of energy that cannot be broken down into anything smaller, but just by being here, we are little clouds of energy experiencing ourselves. Maybe we are the universe creating itself.

Crawling out of CGI snakeskin, incandescent like oil slick, you blink awake to a rainforest coated in slime green LEDs. Little lasers seep out of your fingertips and skull, warding off the hovering fleet of drones; as the RGB smoke cloud clears you sense a cyborg in the distance, easily double your size. Inching closer, across fanning plumes of strelitzia you catch its eye. Inside, a stacked totem of cosmologies: holographic parrot feathers and Roses of Jericho, business shirts and psychedelic cacti, a blind toucan crying into a blind human eye. The cyborg begins to shapeshift into a skyscraper, growing the waxy neon signage of a wellness resort at its base, which is a shrine to finance capitalism, which is built on the ruins of a 15th-century Incan palace and nurtured by plant intelligence, which is an opaque ritual to soothe growing pains of neoliberal bones inside a country that’s turned away from the Earth’s warning signs…

Patricia Domínguez, still from Madre Drone, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Chilean artist Patricia Domínguez explores the hazy cross-pollination of healing rituals emerging from the intersection of multiple worlds through colonial encounters. With a metamorphic practice that spans video installation, sculpture, watercolors, collage, and text, Domínguez unearths the impacts of advanced capitalism on the body and postcolonial rituals for working through it within contemporary Chile. Understanding these processes as intertwined cosmologies that are deeply embedded within a disappearing landscape, and the collective cultural memory of Pre-Columbian South American thought, ethnobotanical traditions, and multi-species relationships, Domínguez stitches together historical rituals and their modern-day manifestations to speculate on possible symbiotic futures for human-and-plant-kind.

First of all, I love the introduction of the term “symbiotic relationship” into the Anthropocene. This helps us to understand that we don’t have to project our anthropocentric ideas of separateness onto ecosystems in order to see that our actions are deeply influencing other species. Instead, we can acknowledge the potential for deep relationships, mutualism, and creative co-creation.

Patricia Domínguez, still from Eyes of Plants, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2019, Domínguez transformed the white-walled space of Gasworks Gallery in South London into an ambient altar for entangling myth, science-fiction, global finance, and consumer electronics within contemporary South America. Washed in hazy neon lighting, towering totems of business shirts and neon braided hair flank a three-channel video installation altarpiece. Two photo-scanned 3D models of the artist’s green eyes – a genetic residue of colonization – flank the 25-minute-long video, Eyes of Plants (2019). Taking a Jarro Pato – a Pre-Columbian duck-shaped vase crying cosmic tears, which sits in Domínguez’s grandfather’s collection of pre-colonial artifacts – as its starting point, the video portals us through a psychedelic narrative that weaves together enchantment and extraction through kaleidoscopic montage.

“Eyes of Plants is about this ritual I’ve been exposed to all my life: images that you cannot articulate in liminal thinking, patterns coming out and intending all of us,” shares Domínguez. “In my work, I navigate all these different worlds by applying a cosmological thinking, a mixed connection to territory. In the process of making, I’m open to whatever happens: I collaborate with whatever comes forward. The healing of plants definitely changed the feeling of the piece – the power of transformation that plants have over a person. It´s a profound modification of one’s hologram.”

Patricia Domínguez, Green Irises, 2019. Installation view. Commissioned by Gasworks. Courtesy of the artist. Photo Andy Keate.

I love the old Mestizo legend about the origin of corn. The humans were short of food, so the earth made the corn plant grow up with lots of delicious kernels for the humans to eat. But the humans were drunk, and ate the whole plant, and when the other plants saw the earth was overtaken with humans, it had to start a war against the humans. This was like the beginning of the world, and now we have to invite the plants into the conversations we’ll have to rebuild our world. Maybe inviting them will cause the other beings to join us, and others to get their shit together.

Wherever natural healing remedies riffing on Pre-Columbian ritual occur in contemporary Chile, global finance and technologically-mediated approaches to wellness capitalism lurk close behind. Sometimes – particularly in an urban context – this entanglement is made literal, architectural. Domínguez cites the multinational bank and financing company Scotiabank’s head office in Cusco, Peru, built on top of the ruins of an Incan palace and flaunting its own archaeological museum, as a reference point.

Other sources are more cosmic and speculative: citing a dream of a souped-up futuristic underground office – its high-earning employees in pinstripe business shirts rendered infantile, cowering on the floor in fetal position, their arms wrapped around Jarro Patos as they cry corporate cosmic tears – Domínguez was led to speculate on the symbolic and aesthetic overlap of Jarro Pato’s maximalist patternation of zig-zags, ripples, and chain-link, and the design of contemporary business shirts, as a kind of psychic amulet for micromanaging the cosmic evils of capitalism (or at least looking nice while brokering deals with the devil).

Patricia Domínguez, stills from Eyes of Plants, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

A tendency to look at the architecture and aesthetics of advanced capitalism runs through Domínguez’s many-tendrilled practice, not least inspired by a visit to Canary Wharf, London’s central business district:

“I spent eight hours walking around and became super interested in these big skyscrapers which had offices in the top floors that never turned off their lights, and healing or meditation centers below ground,” shares Domínguez. “Looking closer, I saw that these temples of neoliberalism are actually decorated with really cosmic symbols: snakes, centaurs. I wondered: what kind of myth are we building? It’s interesting to approach these finance places with a kind of cosmological thinking.”

Parallel research projects like The isle of dogs; a curse in reverse (2017) present this thinking in the form of a sci-fi corporate totem: yoga blocks carved to look like a 3D printed mountainscape, upon which an acupunctured aloe vera, bird feathers, pineapples, incense, a leopard-print tanga and a business shirt coated with emoji stickers are offered up to the speculative tropical gods of Silicon Valley. Dissecting the architectural anatomy of the high-finance high-rise and reassembling it as a postdigital shrine, Domínguez builds a tentative house for the new mythologies merging Pre-Columbian iconography and corporate cosmologies, while underscoring the global reach of this cultural appropriation.

Patricia Domínguez, The isle of dogs; a curse in reverse. Installation at Momenta Biennale de l ́imagen, Canadá, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

As I was interested in how these corporate spaces fold notions of protection into these looping systems of wealth created through so-called “green” capitalist practices, I was thinking of how the powerful re-appropriate the magical thinking to protect and heal, and create a new set of problems through extraction, while celebrating a false form of equality as reflected in the labor of the bodies. I wanted to challenge this mindset with a set of experiments that engaged the audience on an emotional level.

“The browser is the vehicle for the client,” the video’s voiceover cooly explains as psychedelic cacti in a collage of healing technologies undergoes its routine de-spiking by an anonymous health provider in a made-in-China LED therapeutic facemask. “He has 60 inboxes, eight kinds of automatic cancers, seven trash bins and stomachs to digest spam. Within each colon there is a person removing the thorns embedded in the skin, one by one. Within each cactus, there is an Excel sheet. Within the spreadsheets 64 rows are cleaned of the electromagnetic waves that have pierced their bodies.”

Caught between the stuttering verbiage of AI poetics and a posthumanist corporate welcome brief, Eyes of Plants interlaces the parallel damage of neoliberalism and colonialism done to both body and landscape, and the appropriated indigenous healing rituals that have become ensnared in an extended ritual to not just ward off capitalism’s evils, but to live through it. It’s also more complicated than that: Eyes of Plants focuses on the magical presence of roses, which were introduced to South America by European settlers and developed a strong spiritual symbolism within the colonial imaginary through the legend of Our Lady of Guadalupe, who chose the rose as a symbol to manifest herself to Juan Diego, the first indigenous saint from the Americas. Later, it has come to embody a techno-spiritual significance: the rose is used in healing rituals to absorb harmful electromagnetic radiations from Wi-Fi networks.

Patricia Domínguez, still from Eyes of Plants, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

“I wanted to address the rose as a tool of colonization,” explains Domínguez, but also how it’s been folded into healing rituals in Southern America and re-appropriated by those colonized as a form of empowerment. I love this idea of collaborating with roses, it’s a multispecies thing, but really honoring the vegetal intelligence, something to aid our cosmic weariness in the face of neoliberalism, an alternative way to heal the center of our centers.”

This journey of healing our bodies affects the landscape, especially ecological issues, like a fracking project or a dam in Argentina, or a mine in Bolivia; if we approach these issues from the body, through the perspective of plants, we can get a more spiritual and emotional understanding of how hurt places are. By shifting the discussion from the “invisible hand” of the market to the “silent hand” of plants, we can take control of our own lives and protect this planet.

I have this fantasy of planting some rose bushes somewhere else, but I know there’s a ton of problems with some of the roses we have now. And if it’s not in the right soil, it won’t work at all. If we don’t learn how to grow the right plants, how can we expect them to grow us? How can we expect the plants to bring us something new?

Patricia Domínguez, still from Eyes of Plants, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

With Eyes of Plants, Domínguez speculates on a kind of botanic futurism that weaves together family histories and collective cultural mythologies. By combining different scales of thinking, imagining, and myth-making – from the personal to the planetary – Domínguez sows the vision of a shared Earth with new healing rituals rooted in ancestral knowledge systems.

“At the time I made my Green Irises exhibition I was wondering, how do you deal with this kind of whiteness and economic migration in Chile? I needed to make a piece that gets out of it from the inside. When I spat into DNA kits with my grandma for the project, I was thinking about how my body replicates my ancestors in my saliva all the time – how our bodies are so intelligent.” In Domínguez’s work, the flow of information and history is often realized through water – tears and saliva, the lifeblood of both plants and humans, the shared tears of Madre Drone and Jarro Pato, a rapidly privatizing natural resource in Chile – liquids which contain stories, which remember and heal, which bring species together, which unite us all.

It is said that nature and quantum physics, the very fabric of nature, is the result of intent, as this underlying plane of energy that is animating all of nature. I find this very hard to achieve, somehow taking everything into account, from quantum physics to energy work to care and ritual through art, to our ideas of ecology and to bodily aspects of our own being, the way that we absorb our environment and its cohabitation with us. So I am this mestizo as you put it, of all these worlds. I am trying to ask questions and look for new creative forms, freeing myself from this excessive abstraction to reach a more embodied form of creation in which my very being is in the process. I think it requires endless consideration of what it is to be alive in this universe.

Patricia Domínguez, Green Irises, 2019. Installation view. Commissioned by Gasworks. Courtesy of the artist. Photo Andy Keate.

Emerging from Domínguez’s entangled art and writing practice – which has sprouted two publications, Gaiaguardianxs (2020) and Technologies of Enchantment (2019), both designed in collaboration with Futuro Studio – is a new video project, Madre Drone (2020). Flowing seamlessly from Eyes of Plants in the scope and cosmologies of its research and method, Madre Drone tells a story of intersecting worlds in the wake of natural destruction and protest movements in South America. A woman-snake, shedding her serpentine coat in a neon dreamscape of a rainforest to reveal a sci-fi laser superpower, encounters a robot-boy – a kind of cyborg with a green-feathered parrot attaché. A drone’s-eye-view of a rainforest bisected with curving asphalt morphs into a burnt-out forest subsumed by a raging wildfire.

Patricia Domínguez, still from Madre Drone, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Halfway through the film, we encounter a toucan blinded in one eye by the Amazon fires; a 3D model of its wounded vision floats above the glossy facade of a corporate high-rise – followed by a pair of human eyes brandishing the same wound. But in this loss of vision, a clairvoyant superpower gestates: “By losing their eyes, they have transformed into vision machines, perceiving beyond the visible,” suggests the voiceover, as the video cuts to original footage from the student protests in Chile, where protestors used hundreds of lasers to bring down police spy drones. Fighting back against a regime that blinded many of its citizens – both human and not – in protests and vast ecological destruction, Domínguez re-orders and re-encodes these systems into a speculative altar, an alternative vision of cosmic interconnectedness: an eye for an eye, and then – something new.

Patricia Domínguez, still from Madre Drone, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

“I started making Madre Drone as the apocalypse began,” explains Domínguez. ‘From revolts in Chile to a fire in Bolivia, it catalyzed a revolution, to change the system from within, a huge structural change. In the protests, I was looking at the lasers used by protestors to take down the police drone, and I was seeing the drone as a new power animal, a floating eye over the earth, this amazing being that’s spying on us. Even if it represents the police and incarceration, I wanted to have its pixelated vision. Inverting power structures and rethinking conditions for empowerment is important, even if it’s of the imagination, we need a form of vision – a new vision of a system that works for everybody.”

Patricia Domínguez, still from Madre Drone, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

One word to describe a cosmological-spiritual-contemporary approach to reality, with a focus in multispecies consciousness, rituals, planetary memory, inventions, creativity, art, dreams, care, animals, plants, emotions, climate, the living, and the sacred-invisible relationships we establish as humans in regards to humans and other beings and to the planet the cosmos, the quantum particles, is caring.

You are asking literally for a word to describe the way I live my life, which is, I think, a cosmological and spiritual and contemporary approach to reality, with a focus in multispecies consciousness, rituals, planetary memory, inventions, creativity, art, dreams, care, animals, plants, emotions, climate, the living, and on the sacred-invisible relationships we establish as humans in regards to humans and other beings and to the planet the cosmos, the quantum particles. And my word for that is a laugh.

Patricia Domínguez, Madre Drone, single channel video, 2020.