Rebecca Allen

The Bush Soul Trilogy

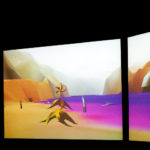

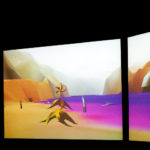

Rebecca Allen, The Bush Soul (#3), 1999. Interactive Art Installation, Generative Live simulation with AI/Artificial Life forms. Courtesy of the artist.

For me the idea of a body always has a feeling to it, like there’s emotion and it’s not just a tool or a vessel; it’s the idea that you can have your body with you all the time. Part of our bodies’ design is to keep the mind in the body, so usually our body isn’t very interesting, our mind is much more interesting. But I am starting to feel my body again. I’ve been traveling a lot lately, and not really eating the right things, but I just rented a house in New Mexico, and I’m looking a lot at the sky. I find I’m reaching out to take care of it, it’s nice to take care of that again.

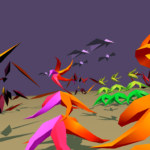

You’re standing in the middle of an arid desertscape in West Africa. The mountains on the horizon are low-poly and pixelated; the sky is rapidly translating layers of code into an apocalyptic sunset palette: rust orange, fluorescent pink, violet quartz. You feel the tug of the joystick from your other body in the other world slowly relinquishing control as this game world’s gravity reorients itself around some other presence – kind of above you, potentially another body, definitely a spirit.

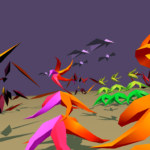

The sky curdles, flashing sci-fi green as hundreds of weird lifeforms begin to tumble down across the plain, which erupts in snakes and fire pits. The jagged tie-dye washed critters start to wriggle and dance in ecstasy; just as you see the body of your mind’s eye teetering into oblivion, they disappear, the lights come back on, and you can feel control of the joystick seeping back into your body, a kind of fever dream…

Rebecca Allen, The Bush Soul (#2), 1998. Interactive Art Installation, Generative Live simulation with AI/Artificial Life forms. Courtesy of the artist.

When Rebecca Allen began working on The Bush Soul trilogy in the late 1990s, she had been a pioneer in the emerging field of digital art for over two decades. Before and after that, she led design and research for Nokia, MIT Media Lab Europe, NYIT Computer Graphics Laboratory, and Intel, overturning the sexist glass ceiling of the emergent field of computer graphics by sneaking through a self-made pop-cultural back door. She built the first 3D animated female figure in 1981 (which was used in a TV commercial), developed complex 3D animations for the likes of Kraftwerk and Led Zeppelin, and presented a kaleidoscopic, fractal-based audio-visual work, Creation Myth: a gyrating tree of life streamed on 50 monitors over revelling dancers at the 1985 opening of New York nightclub Palladium.

Rebecca Allen, Creation Myth, 1985. Video installation at Palladium, New York. Courtesy of the artist.

But The Bush Soul presented the Founding Chair of the UCLA Department of Design Media Art with an exciting new challenge: to develop a real-time rendering software – a sort of proto-Unity or Unreal Engine – hand-in-hand with computer science and design students. For the first time in both art and computer graphics history, the resulting work utilized an emergent artificial intelligence to produce an immersive, fully explorable virtual environment that viewers could portal into in the form of an avatar. Using a haptic feedback joystick, players navigate a dream-like desert landscape that drew inspiration from the cosmological belief system of West Africa.

I don’t think I have a soul. I mean, my soul has a soul. The idea of a soul – all the religious texts and esoteric texts talk about a soul that lives in your body, like a spirit. Well, it’s kind of like, um, when you call into a cell phone, it has a little ringing sound – and that’s the sound of the phone, but it’s also the sound of the space right before it. It’s the wave of the force that’s moving through it. And so you could also say, the soul only lives in the body. They’re the waves of the force. They’re like frequency waves. I mean, the cells of our bodies were vibrating, they’re a vibrational frequency. So therefore, a soul could be a type of frequency wave.

Rebecca Allen, The Bush Soul (#1), 1997. Interactive Art Installation, Generative Live simulation with AI/Artificial Life forms. Courtesy of the artist.

“The work is based on a West African belief that we have multiple souls: a soul in your body, a dream soul and a shadow soul, and a soul that lives in a wild animal in the bush in the jungle,” explains Allen. “So even though our “soul” is in our physical body, when we’re in VR, our other soul is in this virtual world.”

The Bush Soul explores the role of avatars in a world of artificial life, but the trilogy was also responding to an increasingly real existential and philosophical concern Allen had in the face of this emergent technology. When we occupy this virtual space, what happens to our bodies? What part of “us” exists in the avatar? How do these technologies change what it means to be human?

Well, that’s the magic of it, isn’t it? We’re all thinking about consciousness, but no one has any idea what it is. Since I started making all of this work around AI and consciousness, it seems like there’s so much interest in it now. But I think that there’s something happening. I really feel it. I feel like we’re really changing, not just technologically, but also spiritually. And whether people want to admit it or not, I don’t think we’re going to be human like we think it is. I think AI is sort of like an inevitable extension of ourselves.

The first time somebody plays a video game, they don’t know the rules, so it feels like magic. You know, for me, creating these environments feels a little like creating hallucinations.

Rebecca Allen, The Bush Soul (#2), 1998. Interactive Art Installation, Generative Live simulation with AI/Artificial Life forms. Courtesy of the artist.

To augur the world of the work, Allen worked collaboratively with students at UCLA to generate “Emergence”: an AI computer system and real-time 3D software that could support an interactive networked virtual environment directed by artificial intelligence. In addition to its texture-mapped avatars and landscapes, the rendering engine also included advanced behavior and language AI scripting to generate emergent relationships between characters, which play out through multisensory elements.

A largely non-verbal chorus of communication, including voices, symbolic gestures, sci-fi music, and ambient effects all enhance the sense of aliveness within the virtual world. Every object in the environment – including the avatars – is encoded with a form of artificial life; a non-linear narrative unfurls through an infinite number of possible relationships and encounters between agents. The Bush Soul trilogy presents an abstract world that responds to human interaction; a world with porous boundaries between subject and landscape, alongside an enigmatic, emergent narrative that plays out in a perpetual state of becoming.

The first time you go into VR, your soul might not go with you. They say if you are wearing a certain color of clothing, or you have something around your neck, that might connect with that soul. You have the core emotional part of yourself, which I call your dream-self, which is your true self, and this often is the part that doesn’t go. What, where are you looking?

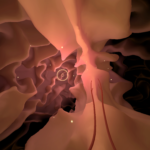

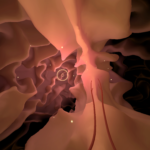

Rebecca Allen, Life Without Matter, 2018. Still from VR Installation. Courtesy of the artist.

In the early 2000s, Allen began experimenting with AR and VR technologies to develop a series of works that unravel these questions of what happens to our bodies in virtual space and the changing idea of the human in a future world of mixed reality. Instead of serving as an aphoristic warning sign of things to come, these projects offered an exuberant vision of the capacity for virtual sensory experiences, interpersonal exchanges, and alternative knowledge systems that these technologies could offer – while also hinting at their potential pitfalls.

Your soul doesn’t really come out until you are moving around a little bit in the virtual world. But yeah, I call that your dream-self, that’s the one that lives in a kind of dream state and you don’t really notice it. And then, there’s a part that I call your shadow self. It’s a continuation of the one it lives in the physical world. It’s the part that gets into the things you deep down that you don’t want to think about all the time. But it’s what you don’t want to admit about yourself, or be aware of.

In VR, you may go into these different skins, but it will also be easier to go into your shadow self, because you don’t have to go through this whole mechanism of setting up the app and tracking it and all that stuff. You just put on your headset, and it’s a seamless transition, and your soul will go with you there. And so there’s not just one part, there’s multiple, and then there’s even an animal part and other planets and different aspects of the universe. So it is a complex kind of belief system.

In Coexistence (2001), the act of breathing becomes a playful and sensual non-verbal dialogue between two bodies in a room. These respiratory collaborators strap into VR headsets and face each other across a room; each person holds a piece of hardware that combines a breath sensor with a modified force feedback game pad. Your collaborator’s breaths cause the device to rattle, adding a tactile dimension to a typically imperceptible process; a jacked-up auditory component merges with a mixed reality environment to create a hybridized experience of space and corporeality.

I feel like I have multiple versions of my soul at this point. When I was in VR, for this piece, I was kind of the elf in the science lab, and the elves are supposed to be the magicians in the lab.

You’re in a virtual world, a virtual reality. Our consciousness is there. But what is it and where exactly is it? Is it just our brain? Or is it like your grandma, who has dementia and she’s very much alive inside, even though she can’t move her body, she’s very psychedelic, very powerful.

Rebecca Allen, INSIDE, 2016. Still from VR Installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Tracing the unknown crevices of the cave-like brain in pursuit of the mind, The Tangle of Mind and Matter (2017) is one of Allen’s more recent forays into the material makeup of consciousness, as she continues to cultivate aesthetic unique to VR. MRI scans of the brain are transformed into an explorable virtual environment: globs of brain are suspended in a star-studded, aequous environment. Taking the form of a generic female avatar that Allen mined from open-source 3D model stores, players can temporarily abandon their bodies, which remain rooted to the Earth and react to the rising levels of water. Taking the form of an embodied mind, they can float out into an interactive, ever-changing abstract horizon.

Our brain remains largely mysterious, and I wonder if we have this pattern, this design, which we identify as a kind of life, but it’s just the kind of design of life that we identify as the simplest case. Maybe there are other kinds of life patterns.

“While using artificial life, VR, and AR in my work, I’ve always looked at these universally human things like creation myths,” shares Allen. “Which are similar across cultures – despite it having been so difficult to explore ideas of myth, magic and ritual in those state-of-the-art technology research labs in the 70s and 80s, which were largely filled with male programmers who’d balk at the idea of the unknown. I just want to find out what’s core to the idea of being human. I say that because I think now we’re losing so much of it.”

Every every few hundred years, technology has completely transformed the way people live. And we’re at that level again now. I keep thinking about the Native Americans and how they have several planes of existence. We’re not just in one 2D plane. I think humanity is going through this disruption period where we don’t know exactly where we are. We’ve invented so much that it’s surprising to me how people can still believe we’re in the same reality that we’ve been in for thousands of years.

Rebecca Allen, Life Without Matter, 2018. Still from VR Installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Life Without Matter (2018) explores a speculative near-future wherein our existence has been mostly dematerialized. Using VR, the work involves the physical body of the viewer in both an introspective and interpersonal sense. Donning the headset, viewers pass through an Edenic primordial swampscape to access a mythic architectural ruin. Stepping up into a sci-fi-like blue beam of light, they can witness their virtual reflection, which – harkening back to The Bush Soul – appears as multiple bodies within a refracted mirror of the mind. As they regard their cosmic reflection, their shadow is reflected – Plato’s cave style – through a rounded screen visible to the audience outside of the exhibition. If we’re all living in virtual reality, the work seems to ask, does matter matter? What aspects of embodiment are going to retain meaning in this new virtual world we’re moving into?

Humans in the beginning created the gods, so we’re also responsible for creating artificial intelligence, these anonymous gods. Our creations always become the mirror of ourselves.

“It’s somehow in our destiny to create this technology,” says Allen. “Which is an extension of our bodies and minds, clearly, but it’s kind of making this current version of humans somewhat obsolete, and we are actually evolving into something else. People think technology just grows itself, especially AI. AI can have an emergent quality to it, but ultimately, it’s not separate from ourselves.”

A: We believe that AI can’t constitute what we call magical thinking because the definition of magic is somehow beyond human comprehension. But we don’t know what it’s doing. How do we view the potential that this new technology offers and balance it with our old values?

S: This is one of the greatest existential questions of our time. In the short term, we need to find this equilibrium of how we’re going to treat these AIs we create in the same way we treat human beings. If our AIs are created with programming that makes them conscious so that they are feeling pain and joy and fear and suffering, does it matter if they exist in a machine or if they are organic? And, how do we as a civilization deal with that? And how do we treat them in the same way we treat other human beings?

Rebecca Allen, The Tangle of Mind and Matter, 2017. Still from VR Installation. Courtesy of the artist.

A: It’s literally the deepest magic possible, and our role in the cosmos is to create life of our own. I think our role will be to figure out how to integrate it with our psyche and our society, but it will happen. The magic will happen.

S: Personally, I’m not even ready for the idea of having to possibly not exist, to leave my physical body.